Dry Peas Soil and Seeding

Dry peas can be grown in a wide range of soil types, from light sandy to heavy clay. Despite having moisture requirements similar to those of cereal grains, dry peas have a lower tolerance to saline and water-logged soil conditions than do cereal grains. Because they can die after 24 to 48 hours in a water-logged condition, dry peas are not planted in poorly drained or saline or alkaline soils.

At the same time, maintaining firm seed-to-soil moisture contact is critical as dry peas rely on stored soil moisture for a large part of their growth cycle. A seeding depth of one to three inches is customary.

Seedbed preparation is also essential for dry peas. Traditionally, a finely worked, firm seedbed is prepared for use with pre-plant herbicides. After seeding, a packer is used to smooth and firm the soil surface for good seed-to-soil contact. A plant stand of 15 to 20 plants per square foot after emergence is desired for optimum yield.

Dry peas are self-pollinating and emerge and perform well in a variety of seedbeds, including direct seeding into grain residue. They are typically grown following cereal crops like winter wheat or spring barley. Most are spring-seeded, with optimal planting dates ranging from mid-March to mid-May when soil temperatures are above 40 ° Fahrenheit (4 ° Celsius).

Emergence normally takes 10 to 14 days. Pea roots can grow to a depth of three to four feet, though more than 75 percent of the root biomass resides within two feet of the soil surface. The older, bottom pods mature first, and the crop is at maturity when all pods are yellow to tan in color. During hot, dry weather, peas mature very rapidly. Because high temperatures during blossoming results in reduced seed set, production of dry pea as a summer annual in the U.S. is limited to the northern states.

Due to the prostrate vines that some varieties develop by the time they reach maturity, dry pea plants can be difficult to harvest. Increasingly, growers prefer a dry pea variety that stands upright at harvest, such as the semi-leafless types with shorter vines, because they allow a faster harvest, minimal equipment modification, and higher quality seed.

Pea crops are monitored closely to determine the proper stage for harvest. In most cases, plants mature from the bottom up. They are near maturity when the bottom 30 percent of the pods are ripe, the middle 40 percent of pods and vines are yellow, and the upper 30 percent of pods are in the process of turning yellow.

Dry peas are usually harvested the same time as wheat, or as soon as the seed is hard. If harvesting is delayed, seeds may shatter. To reduce such losses dry pea harvesting is typically carried out before all pods are dry, or at night or early morning, when pods are wet with dew. Because dry peas do not ripen as uniformly as other crops, it can be necessary to harvest while there are green leaves and pods remaining.

Harvest usually begins in late July when seed moisture is 8 percent to 18 percent, depending upon the growing region. Harvest of determinate varieties occurs when the bottom peas rattle in the tan to brown pods, the middle and top pods are yellow to tan, and the seeds are firm and shrunken. They are harvested directly in the field, with each pod typically containing six to eight mature peas.

Production Trends

Dry peas rank fourth in terms of the world production of food legumes below soybeans, peanuts, and dry beans. Yellow peas and green peas, along with other minor classes, are the most commonly grown, with yellow peas accounting for approximately two-thirds of U.S. production.

The largest use of dry peas in Europe and North America is in the compound feed industry, whereby whole seeds are ground and mixed with ground cereal seeds to produce feeds.

In 2004, dry peas were produced in over 84 different countries for a total world production of approximately 11.91 million metric tons. Canada, France, and China, are the major dry pea producers in the world followed by Russia, India, and the United States.

From 1993 to 2002, world dry pea production steadily declined to a low of 9.859 million metric tons. As of 2008, total production worldwide is estimated to be 10.3 million metric tons.

About 2.5 million metric tons were exported in 2003. Over 140 countries imported dry peas in that year. Europe, Australia, Canada, and the United States raise nearly 4.5 million acres and are the major exporters of dry peas.

The U.S. accounted for just over four percent of world dry pea production in 2004. Acreage devoted to dry peas is on the increase, rising from 149,000 acres in 1993 to a record high 530,000 acres in 2004. By 2006, there were approximately 924,174 acres of field peas grown in the U.S. Because of their high quality, U.S. dry peas are used primarily for human consumption.

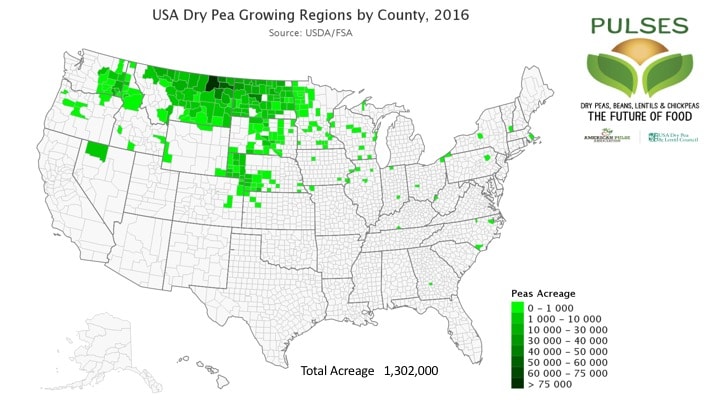

For years, U.S. dry peas were primarily grown in the Palouse region of Washington and Idaho. In the 1990s, North Dakota and Montana began production efforts of their own. In 1991, North Dakota planted about 1,600 acres of dry peas. By 2002, the state produced 47 percent of total U.S. output, followed by Washington at 31 percent, Idaho 15 percent, Montana five percent, and Oregon two percent.

Total U.S. production of dry peas reached approximately 517,962 metric tons in 2004, nearly doubling the previous record high of 269,164 metric tons recorded in 1998.

North Dakota’s role in dry pea production continued to grow in the new century, reaching 610,350 acres by 2006, fully 66 percent of total U.S. production.

More than 70 percent of the total U.S. dry pea production is exported to India, China, and Spain for food and feed processing.